Shadow of a Wheel

/Paul receiving his emmy for Best Historical Documentary.

Updated March 2025:

Since this story was originally published in 2023, Paul Bonesteel’s documentary, Shadow of a Wheel, has been awarded a Regional Emmy as Best Historical Documentary. Paul grew up in Flat Rock and is the son of well-known Flat Rock residents Georgia and the late Pete Bonesteel.

Paul will speak at Flat Rock Village Hall on March 16th about his latest book and documentary project about noted western North Carolina photographer, George Masa. Details here.

—-

Paul Bonesteel, age 57, still rides his bike on the backroads and trails of western North Carolina. On sunny days, when he looks down at the pavement below his bike, he sees the shadow of his wheel spinning towards the crest of the next hill or the next bend in the road. And each time he sees that shadow, Paul is invariably taken back to the summer of 1982 when he was a Flat Rock teenager making an epic journey that would be one of the defining moments of his life.

Today, Paul Bonesteel is an accomplished documentary filmmaker living in Asheville pursuing his passion for history, nature, music and personal storytelling. The many films his company has produced over the course of the last three decades are a testament to his commitment to telling stories that illuminate and inspire. His catalog of films includes documentaries about Carl Sandburg, Carl Schenk, Asheville’s first desegrated municipal golf course, and The Great American Quilt Revival which features his mother and Flat Rock resident Georgia Bonesteel.

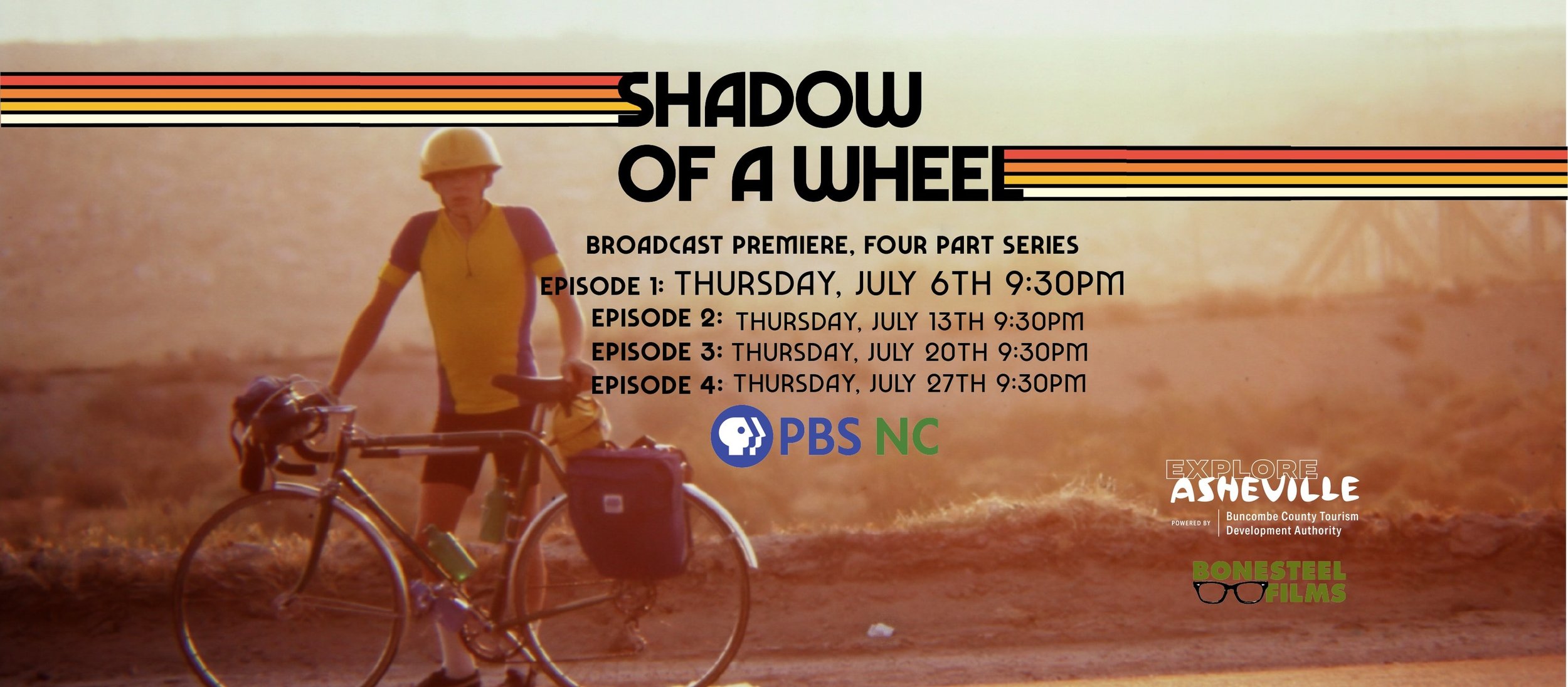

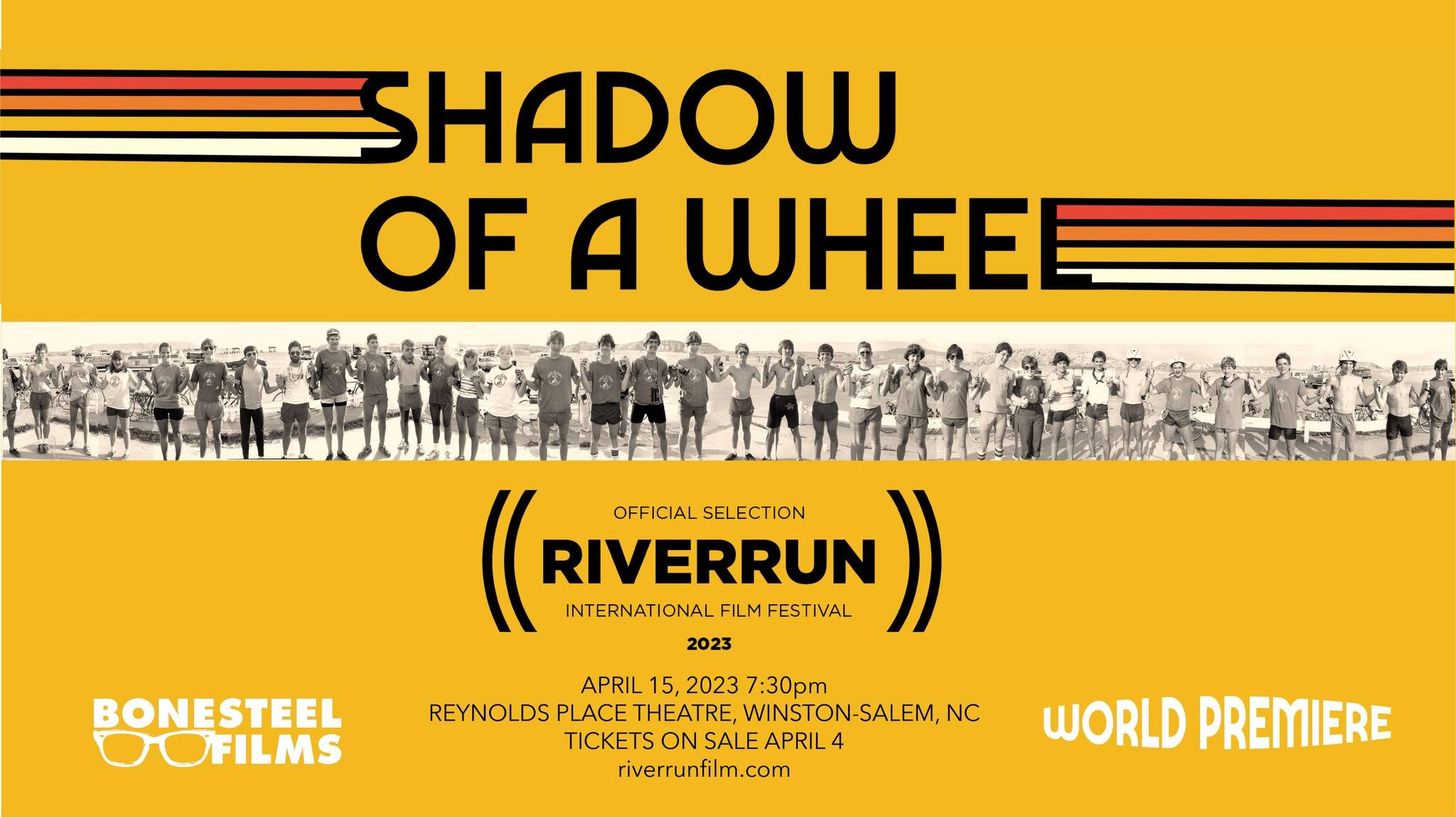

This year, Paul and his company, Bonesteel Films, released its latest documentary - and perhaps the most intensely personal work Paul has ever created – Shadow of a Wheel.

—-

Paul Bonesteel

In the spring of 1982, Paul Bonesteel was a 16-year-old rising Senior at Henderson High School and living with his family in Flat Rock. He was also a young man possessed of a dream that very few of us would ever dare to contemplate. He was preparing to embark on a cross-country bike trip from Long Beach, California to Cape Hatteras, NC.

It was to be a two-month-long cross-continental journey over mountains, through deserts, across endless prairies, in the blazing sun and in the pouring rain. It was a ride through the congested city streets of major metropolises and along the rural backroads winding from one small town to the next. In short, young Paul Bonesteel was about to experience the fullness of America – one mile at a time from the seat of his bike for 3,600 miles.

—-

The trip was conceived and organized by a young man named Chuck Williford who hailed from Hickory, NC. Chuck was an avid biker who had personally accomplished a cross-country trek with friends. He presented his dream of a cross-country youth pedaling odyssey to the Multiple Sclerosis Society of North Carolina as a fundraiser for the Society. The Society was intrigued and agreed to partner with Chuck in the expedition.

Chuck immediately went to work to find riders willing to tackle the trip. He posted ads in newspapers across the state looking for willing riders who would also be able to raise about $5,000 in sponsorships. One of the cities Chuck visited was Hendersonville. He placed a small ad in the Times-News which gave the place and time for an information meeting to be held in the old City Hall on KIng Street. One person who saw the ad was Flat Rock resident, Georgia Bonesteel. An avid biker herself, the announcement sparked Georgia’s interest and she showed the ad to her son.

—-

Paul Bonesteel, Age 16

Paul spent much of his youth on a bike exploring the roads and trails of Flat Rock and Henderson County in a young boy’s pursuit of adventure and independence. The trip proposed by Chuck Williford seemed to both mother and son as something within the realm of possibility. It was also a time when children were perhaps not as tethered to their parents as they are today. “Being the third child it was only natural that we let him ‘do his own thing’ many times,” recalls Georgia.

Paul and his parents showed up at City Hall on the appointed day along with about 10 other teenagers and their families. Chuck had a slide show of his biking adventures and his passion and enthusiasm for the trip cemented Paul’s desire to go. He looked around the room nervously, thinking he might be in competition with the other teens in the room for a slot in the group. He need not have worried, however, as only two of the ten kids in attendance followed through on the challenge – Paul and Randy Wulff.

The Spokesmen for America, 1982

Ultimately, Chuck Williford’s passion and charisma were intriguing enough that 31 North Carolina teenagers signed on for the trip.

***

The first part of Paul’s odyssey did not involve a bike. The young teen was tasked with raising $5,000 to cover trip expenses with the balance to be contributed to the MS Society. Before he could pedal, Paul would have to peddle the idea of sponsorships to neighbors, friends, local businesses, and anyone else willing to support his cause.

He wrote letters to friends, family, and acquaintances. He went door to door asking for donations – typically requesting $36 - or one penny per mile of the proposed trip. He approached local businesses for sponsorships. His quest was so well known that he was stopped on the street in downtown Hendersonville by a stranger that recognized him and handed him a $100 check on the spot. The final $500 of the total was raised when Paul and friends went out and planted trees for a weekend on a Christmas tree farm. “We were digging holes and putting the seedlings in and I don't know how many thousands of Christmas trees we planted,” Paul remembers with a smile.

Paul’s persistence had paid off. He was ready to make the trip.

***

In a sense, Paul had been training for the ride his entire childhood. The family lived on Estate Drive off Rutledge Road and Paul would ride a loop from Rutledge to Greenville Highway to Little River Road and then cut across Kanuga Road to Laurel Park and eventually up to the top of Jump Off Rock. Then he would wind his way back home. His training rides were typically 15-20 miles. And even though the average daily distance during the cross-country ride would be 60-70 miles, Paul was confident.

He was also excited about tackling a challenge so unique. “I generally like challenges for some strange reason. I wanted a risk or adventure that was different from what my siblings and my friends had going on.”

Paul was physically prepared to make the trip. The emotional part of the ride would be another challenge entirely – as he learned over the course of the 56 days and 3600 miles.

—-

Parents of the Riders at the Charlotte Airport

The adventure began when the intrepid pack of teens and their adult support team flew from Charlotte to Long Beach, California where they would start the trip. In the airport waiting to watch her son depart, Georgia Bonesteel recalls that the magnitude of the trip became very real. “We did have our angst and worry, but that did not come to a head until we got to the Charlotte airport. We had no means of communication as today with cell phones.”

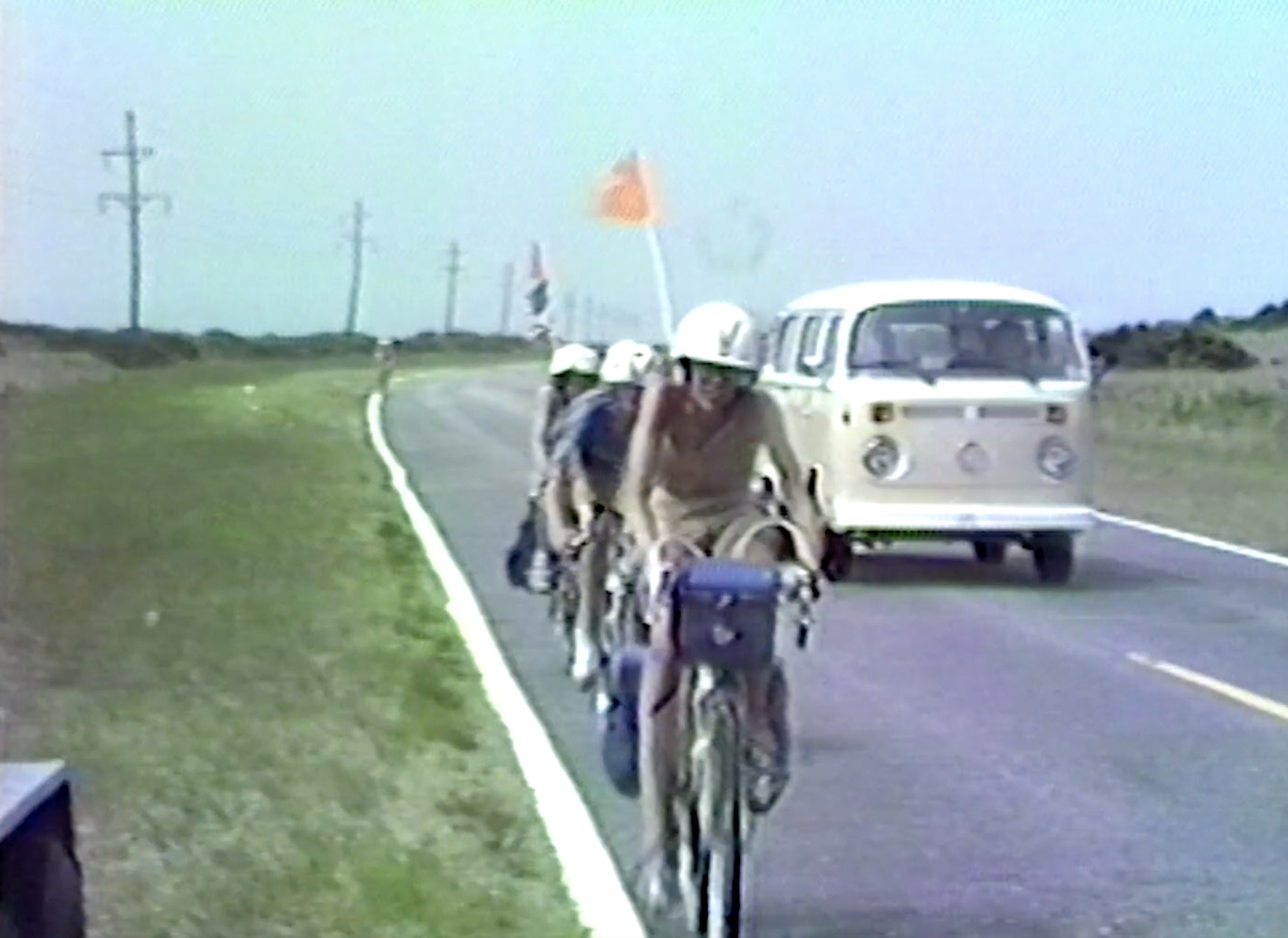

The group called themselves the Spokesmen for America and they started from the shores of the Pacific Ocean on June 19th, 1982 and headed east – the only direction they would think about for the next 56 days. It would be August 13th when they pedaled the last mile of their 3600 mile trek.

During the trip, the group would cross the Mojave desert, visit the Grand Canyon, traverse the Rocky Mountains, and even ride under the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. They tackled every day with one goal in mind the entire time - Cape Hatteras.

As Bill Moss wrote in The Hendersonville Lightning:

Adventures were countless and often harrowing: pedaling through sun-drenched 130-degree heat, stinging sandstorms and brutal headwinds, climbing 10,850 feet to summit the Rockies, outrunning thunder and lightning in Kansas, enduring road hazards, drafting behind tractor-trailers, suffering from homesickness, saddle soreness, hunger and thirst.

Through it all, the group persevered. “It scared us sure, but Chuck never portrayed the trip as impossible. So we didn't see it as impossible either,” says Paul. The 31 teens were shepherded by five adults who oversaw logistics, rode with the kids, followed along in a support van, and generally worked to keep the group reasonably safe and healthy despite the rigors of the road.

Randy Wulff sleeps on the sidewalk in front of a restaurant. (Photo by Rick Foster)

The kids slept in fields and yards and occasionally overwhelmed small-town diners with their numbers and voracious appetites. They also accomplished the trip without the advantages of today’s technology. “We knew how to fold up a paper map and how to use a pay phone,” Paul says with a rueful smile.

Back home, without the benefit of regular contact, Paul’s parents kept tabs on the group's progress with a map on the wall in their Hendersonville hardware store. They used pins on the map to track the group’s progress and to have some sense of where they assumed their son was on any given day.

***

Paul Bonesteel started recording the world around him in 8mm film when he was 10 years old. Georgia remembers those early efforts of her budding filmmaker. “We all recall Paul doing silly home movies on the garage floor of our home. The main character was Gumby—the silly green figure that kids played with. There was no doubt he would do documentaries.”

Paul left Hendersonville to study communications at NC State University with a concentration in Video Production. After school, he spent a few years in Atlanta in various jobs in the industry before returning to Asheville in 1997. “I’ve done many types of projects, but documentary films have been my passion and art since my first one in 1990.”

Paul Bonesteel

Today, Paul has directed more than a dozen documentary films including an award-winning film for PBS’ American Masters on Carl Sandburg and the 2021 film, Muni, telling the story of Black golfers and desegregation on a public course. From Alaska to the Soviet Union to Africa and to the mountains of North Carolina where he grew up, Paul’s storytelling is both local and global, but always filled with the enthusiasm and commitment of 1982’s bicycling adventure.

***

Thirty years after the trek, in 2012, Paul was able to acquire some of the dozens of videotapes recorded that summer from Chuck’s father. Unfortunately, many of the tapes had been taped over to record TV programs during the intervening years. Enough of the video survived, however, to take Paul and his fellow riders right back to that summer and rekindle many long-dormant memories.

That same year, several of the riders marked the 30th anniversary of their trip with a reunion at Cape Hatteras. “A bunch of us reconnected and reflected on what the ride had meant,” Paul recalls. The seed of a new film project took root in the back of Paul’s mind during the course of the next several years.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, the inevitable slowdown in Paul’s normal business schedule gave him time to revisit the project. And this time he approached the challenge with the optimism and tenacity that had defined his 16-year-old self. The project was also therapeutic. “I just needed to remind myself that I had been through hard things, and I could do hard things again.”

It was time to make Shadow of a Wheel.

***

Paul used the available video, interviews with several of the participants, and recollections collected in the tattered and faded journals that he and the other riders kept during their cross-country ride to put together the four-part series currently available on PBS. For Paul and his friends, it was an opportunity to relive the ride, but also an important opportunity to remember where they had been and how far they had traveled in their personal lives since that day when they peddled the last mile of their trip to the base of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

The film vividly portrays the challenges of the trip - the hardships and physical suffering that riding a bike for 3600 miles entails. It also catalogs the emotional turmoil that so many of the teenagers felt during the trip. The film examines their struggles with relationships stressed by the crucible of such an epic undertaking and the emotions of being so far away from family and friends in unknown parts of the country.

During the daily rides, the group would invariably split up and the riders could be spread out over as much as 30 miles of road. “For long stretches of the ride, it was just you, your bike, a patch kit and a pump. There was the feeling of loneliness out in the middle of nowhere,” says Paul.

The group arriving at Cape hatteras

When the last miles of the trip arrived and the Hatteras Lighthouse loomed in the distance, the already emotional nature of the adventure took on a different meaning as the teenagers realized they might not ever see each other again. “There was a little bit of, 'Oh crap, I'm about to say goodbye to all these people!’” explains Paul. There was also relief. “I was ready to put the bike on the car and go home. I'd had enough because I had just given it everything I had.”

Sadly, the kids had no way of knowing that after they parted ways at Cape Hatteras, they would never see Chuck again. A private pilot, he died in a plane crash in November of that year at age 28.

***

Paul and his fellow riders celebrate the end of their journey across america.

The documentary is, in the end, a fascinating look into the minds of teenagers faced with a daunting challenge in an epical coming-of-age experience. Not surprisingly, the riders who sit for interviews with Paul during the documentary speak passionately about the life-long impact of the experience over the course of the next 40 years of their lives.

And, as a viewer, it’s hard to watch the film, listen to the participants, and not end up wondering, “Could I have done that when I was a teenager?” For Paul, making the film was an important means of processing what the ride meant to those 31 kids. “You don't really see those moments the same at the time as you do 10, 20, 30 years later. Sometimes you cannot fully appreciate what was going on until much, much later."

Paul adds, “I wasn't the only one that said in the interviews that the ride meant a lot at the time - but it means even more now.”

***

Paul riding his bike in the Blue Ridge Mountains

Shadow of a Wheel was released this summer and Paul has been pleased by the response. He’s also grateful for the opportunity to revisit such a seminal time in his life. “Whenever I get on my bike now, I look down at that shadow on the road and it immediately returns me to the summer of 1982." Paul pauses in thought for a moment and then concludes, "I still love to ride because it helps me stay connected to that important time in my life.”

——

Shadow of a Wheel is available to stream on PBS North Carolina. Learn how to watch the documentary at https://www.pbs.org/show/shadow-of-a-wheel/

Learn more about Bonesteel Films at https://www.bonesteelfilms.com