From Waterloo to Flat Rock

/This was the very first post of Flat Rock Together from July 2019. Updated here with additional information about the Royal Scots Greys and with an excerpt from Louise Howe Bailey’s history of St. John in the Wilderness.

On a Sunday morning in June of 1815, Scotsman James Brown found himself staring across the countryside of Waterloo, Belgium. A bugler for the Royal Scots Greys, Brown clutched his instrument and prepared to enter battle against the famous French army of Napoleon Bonaparte.

“Scotland Forever” by Lady Butler depicts the start of the cavalry charge of the Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 during the Napoleonic wars.

Brown’s role was to convey his commander’s orders to the troops via the notes he played on his instrument. As the cannons reported across the countryside, British and Prussia soldiers clashed with their French counterparts. The fighting was fierce and always conducted at close range - often hand-to-hand combat.

After a full day of attacks and counterattacks by both sides, the French army was routed and the Napoleonic Wars were finished. In particular, a heroic charge by the Royal Scots Greys was a turning point in the battle and is considered a defining moment in the regiment's history. Wellington went on to a life and legacy of glory as the victorious general who finally vanquished Napoleon. Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba.

Just a few years later James Brown, witness to perhaps the most iconic battle in European history, immigrated to America. Ultimately ending up in Flat Rock, NC.

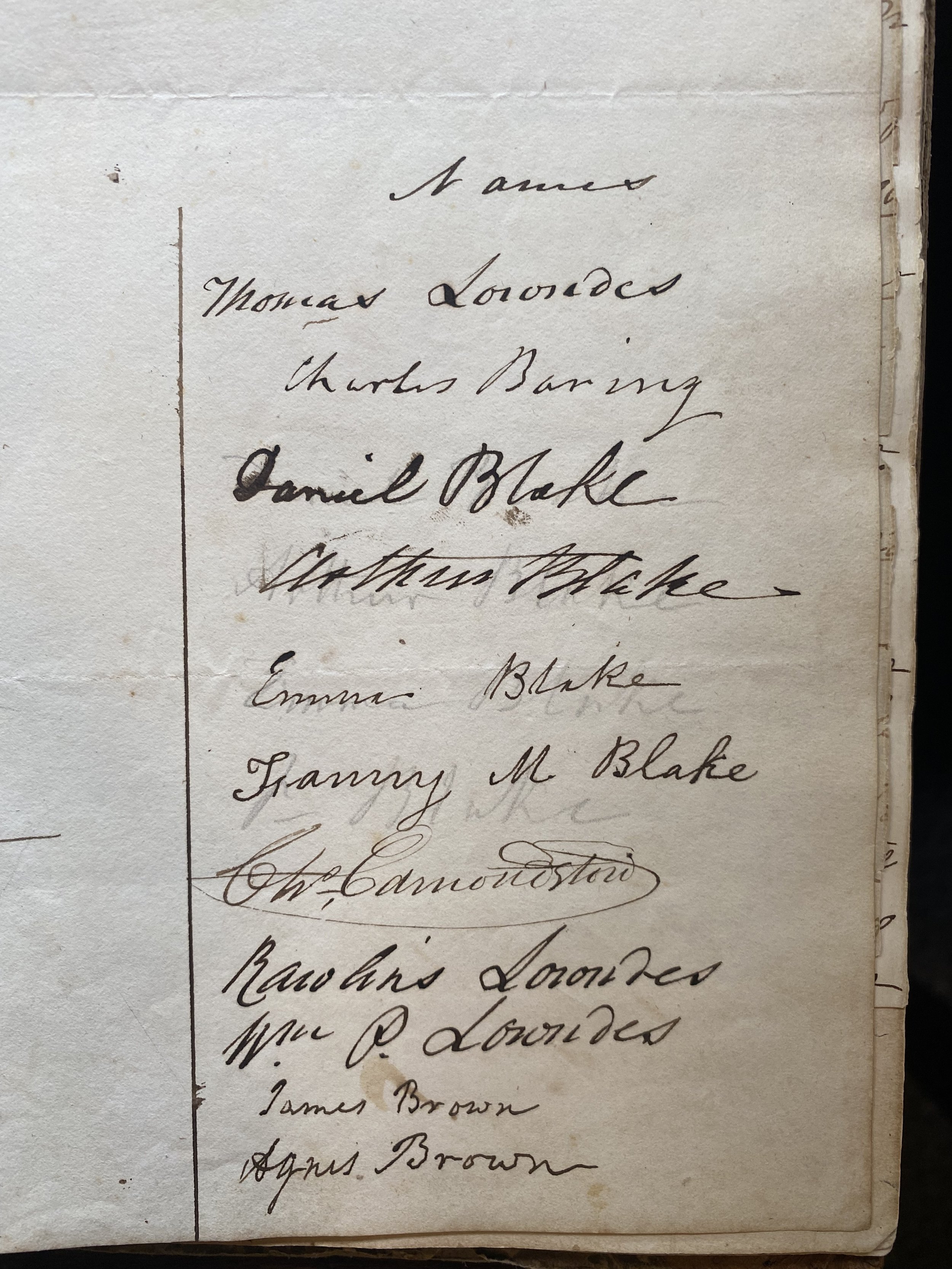

“We, the undersigned inhabitants of Buncombe County, residing near Flat Rock, do hereby form ourselves into a congregation under the title of the Church of St. John in the Wilderness and promise conformity to the Doctrines, Discipline and Worship of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States and also the Constitution and Canons of the same church in North Carolina.” St. John in the Wilderness Vestry Book 1836

Brown was employed by Charles Baring who lived in Charleston and served as a representative for the Baring Brothers banking family in England. Baring’s wife, Susan, found the Charleston summers oppressive and they built Mountain Lodge, one of the first two homes built in the summer colony of Flat Rock. Brown came to Flat Rock with the Barings and spent his summers working for them at Mountain Lodge.

Brown worked for the Barings and worshipped with them at St. John in the Wilderness - a church the Barings built to serve as their spiritual home during summers in Flat Rock. In fact, James and his wife Agnes were among the 20 signatories on the document that formally created the church in 1836

Brown spent summers with the Barings in Flat Rock until his death in 1840 and was buried at St. John in the Wilderness. His grave was covered with a brick masonry structure that was then topped with a marble slab. This structure still exists and is directly adjacent to the historic church.

Eventually, Brown’s body was disinterred and returned by his family to his ancestral home in Scotland. But the brick edifice above his former grave remained - and went on to be the source of many interesting stories.

Louise Howe Bailey wrote of Brown in her book, St. John in the Wilderness:

“Immediately outside the carriage entrance is the grave of James Brown, once a trumpeter with the Royal Scot’s Greys at the battle of Waterloo. With his wife, Agnes, he came to Flat Rock as a member of the Baring’s household. His name, and that of Agnes, are listed among the names of those who “form themselves into the first congregation of Saint John in the Wilderness.”

Across the years it has been rumored that on stormy nights when thunder rolls, the sound of a trumpet can be heard echoing from James Brown's grave.”

Albert Gooch at the original Gravesite of James Brown.

Albert Gooch, who once served as Head Docent at St John in the Wilderness and past President of the Kanuga Conference Center, shared another interesting version of the legend of James Brown’s grave:

“Despite the fact that James Brown’s body had been disinterred, the church kept the brick edifice that had covered his gravesite. Later, during the era of prohibition, local moonshiners decided that it would be a great place to distribute their wares. They would take orders and come to the church in the dark of night. They would raise the marble top on the old grave and leave the moonshine in the empty space below. Then they would retire to a discreet distance and wait for their customers to pick up their purchase and leave payment in the gravesite. This went on for a long, long time until prohibition finally ended in this country.”

After prohibition, Brown’s grave served a more frivolous purpose according to Albert - one of Flat Rock’s most famous storytellers. At Halloween, children of the church discovered that they could lift the marble slab and crouch in the empty space below. When they heard someone approach, they would lift the slab and scare the unsuspecting passersby. This practice ended, however, when the marble top eventually cracked and an iron fence was built around the gravesite.

Today, Brown’s gravesite is adorned with a Union Jack flag that is always displayed to honor the memory of the man who fought at Waterloo and went on to live in Flat Rock, NC.