Building Rock Hill

/The following article has been excerpted from the Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site, Connemara Main House, Historic Structure Report published in September of 2005; created by the Historical Architecture, Cultural Resources Division of the National Park Service.

The report is a comprehensive overview of the history and structure of the Carl Sandburg Home from the days of its construction in 1838-39 by Christopher G. Memminger up until the 21st Century.

The content presented here is a very small portion of the overall report and deals with the construction of the home Memminger called “Rock Hill” - later to be known as Connemara. The full report is online (link here) and it is a fascinating study of one of Flat Rock’s most important historical homes.

Please refer to the report directly for the many sources used to compile the report. This article was taken primarily from sections entitled, “Historical Background and Context, The Memmingers” pages 5-25. And, “Chronology of Development and Use, The Memminger’s Rock Hill” pages 50-62. BH

—

“What a hell of a baronial estate for an old Socialist,” Carl Sandburg remarked after purchasing Connemara in 1945. Originally called Rock Hill, the Main House that is the centerpiece of the estate is located in Flat Rock, one of the earliest and most famous of the summer resort communities that have been a feature of western North Carolina since before the Civil War.

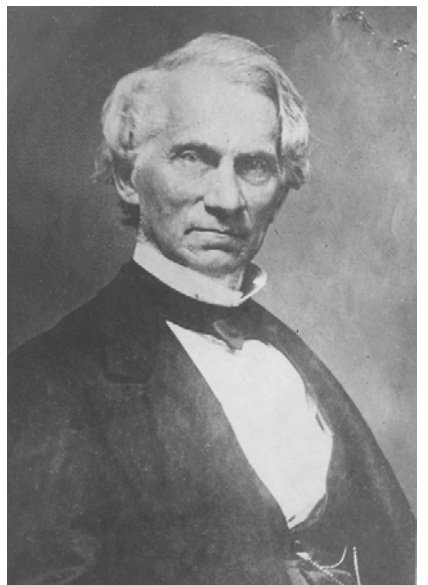

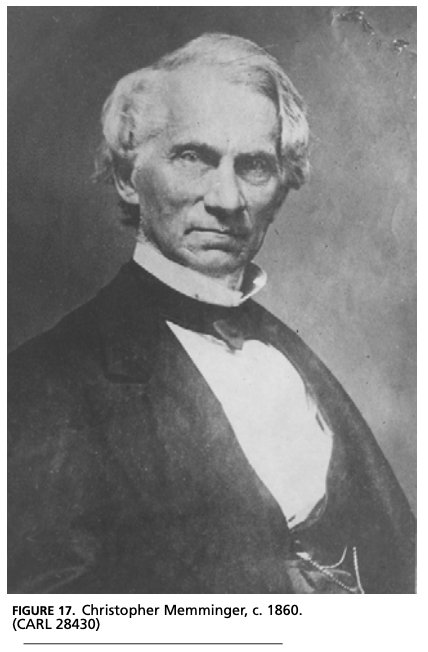

The house was built in 1838-1839 by Christopher G. Memminger (1803- 1889), a wealthy lawyer and politician from Charleston who later became Secretary of the Treasury for the Confederate States of America.

—

Christopher G. Memminger Ca 1860

Christopher Memminger’s first recorded visit to Flat Rock came in the fall of 1836, although he may have visited earlier. It was during that visit that he apparently determined to build his own summer home at Flat Rock.

Memminger wrote:

Of course, the firstcomers (To Flat Rock) had the best for residences. But as I also wanted a farm I could not be so easily furnished as the land near Flat Rock is miserably barren. Nevertheless, after much cruising, I at last found a place that would suit very well and authorized the Count (de Choiseul, owner of Saluda Cottages) to purchase it if it could be had, on Mr. Baring tendering to let me have some of his contiguous land and the use of a spring from an elevation of his land.

We also sketched the plan of a kitchen to be built for our occupation next summer on the spot,- - - a project by the way which I am rather doubtful about because my kitchen is rather too fine an affair. I ought to hire Mr. King’s house if possible and build at once.

Events intervened, however, and Memminger’s plans appear to have been laid aside, due perhaps to the great financial panic that unfolded in the winter and spring of 1837. Memminger apparently had come to some agreement with Charles Baring for the land that he wanted, although he did not actually take title until November 1838.

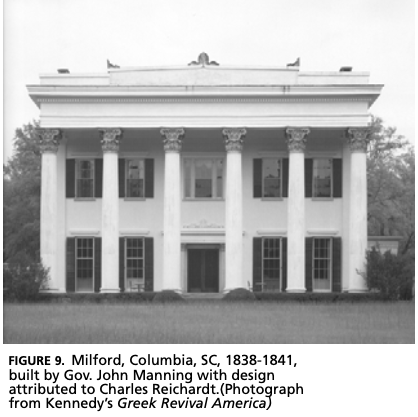

By the end of 1837, he had begun preliminary work, including construction of a bridge across the creek that later formed Front Lake and perhaps leveling a building site in the hillside above. Perhaps as early as late 1837, but certainly by the spring of 1838, Memminger had engaged the services of an architect to design his house and, in the first week in July, paid Charles Reichardt fifty dollars “for plans.”

Design

Memminger could not have chosen a more fashionable architect than Charles F. Reichardt. Unfortunately, no documentation exists for their relationship beyond a single account book entry, which appears to have been entered after the fact, noting that Memminger paid fifty dollars to “Reichardt for plans” in July 1838. Nothing has survived of any drawings or specifications that Reichardt might have produced for Memminger.

In January 1837, the Charleston Mercury had announced: “that the plan for the New Hotel by Mr. Reichardt having been chosen, a contract was made for its immediate execution.” It would have, the paper reported, “fourteen colossal Corinthian columns and be unsurpassed in taste and elegance with any similar building in the United States.”By the end of March 1838, the hotel was nearing completion and “a celebratory dinner” was held in anticipation of its opening. Within days, however, the hotel was gutted by fire and hundreds of other buildings were destroyed in one of the city’s worst conflagrations.

Memminger had probably already set his sights on a Greek Revival design prior to contacting Reichardt, which is not surprising given the acclaim surrounding the Charleston Hotel, the reconstruction of which after it burned in April 1838 was getting underway only a few blocks from Memminger’s house.

Original Characteristics.

The original house included the present stone foundation and a wood-framed story and a half above that. There were at least two brick chimneys, ending in simple corbeled courses without the arched brick flue covers that were added at a later date.

Much of the original 5” wide lap siding remains intact, but the original roof covering would most likely have been wood shingles. The deeply molded corner blocks and casing on the front of the house are original features, as is the plain beaded casing that was used at the windows on the sides and presumably the rear of the original house.

Materials

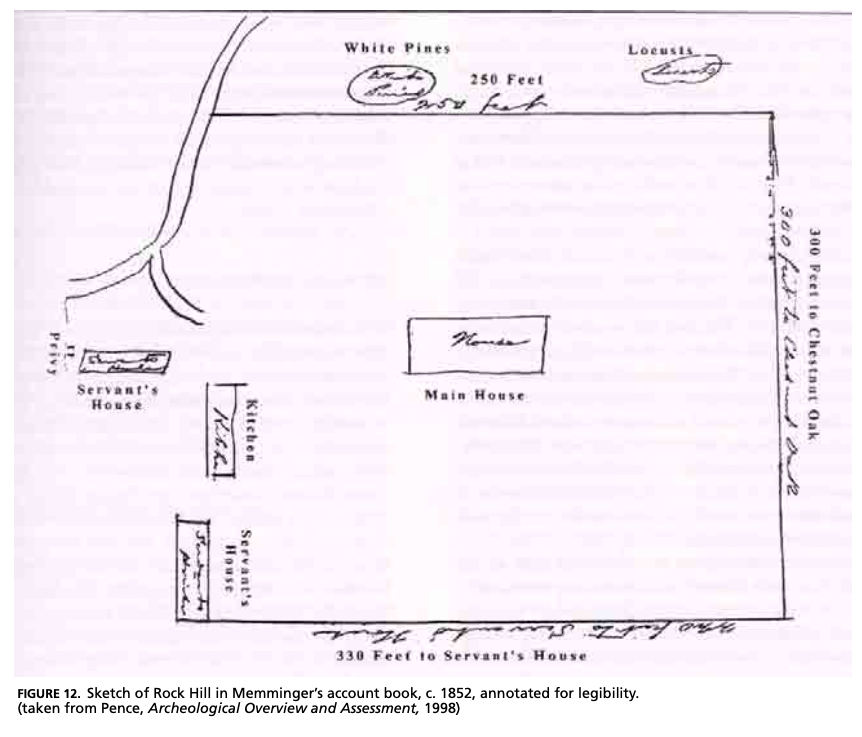

Sketch of Rock HIll from Memminger’s account book ca 1852

Memminger’s son Edward recalled that “in early days, before dynamite, the quarry on Tranquility was the only workable quarry in the settlement and it furnished rock for most of the houses built at that time.”

Only later, apparently, did the more prominent quarry near the present Flat Rock Playhouse come into operation. An enormous amount of stone had to be hauled up to the building site, and on 18 April 1838, Memminger paid a hundred dollars for a yoke of oxen and a cart. There was apparently more work than the oxen could handle, and in July, he bought a pair of mules and a wagon as well. His account book records the constant use of these animals, which sometimes made trips as far as Green River to retrieve materials.

Memminger’s son also recalled that “at the time fine work was not possible, so the house was built from hewn sills and beams... the same being true of all pioneer settlers.’ In this, he was slightly mistaken. True, the house was built with hand-hewn sills and beams, but the bulk of the lumber, including joists, studs, and rafters, was mill sawn, almost certainly at one of the nearby sawmills. Brick, too, may have been produced locally as well, although by whom, we do not know. The source of neither the brick nor the lumber can be determined…

Memminger paid for nails (500 pounds in 5 kegs), paint, glass, lime, millwork, and hardware, some perhaps through local suppliers, but all ultimately shipped from Charleston by train to Aiken and then by mule- or ox-drawn wagons the rest of the way.

Some of the woodwork, including the two-panel doors and some of the simpler moldings, may have been made … on-site, but the deeply molded casing and corner blocks used at window and door openings on the front of the house and on primary interior elevations were largely machine-made and probably shipped in from Charleston.

Construction

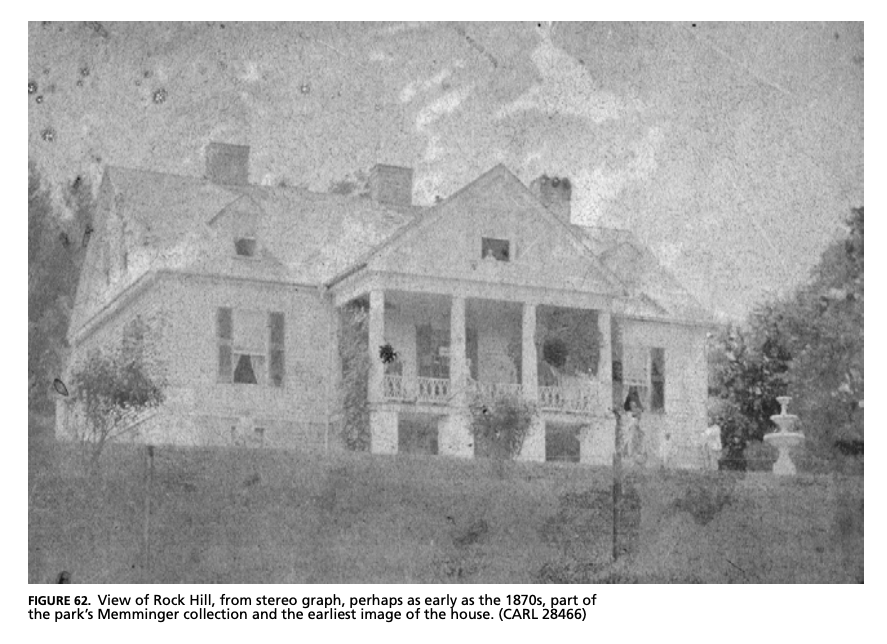

Earliest image of Rock Hill

Although Memminger did not begin his account of expenditures at his “Buncombe establishment” until 1 April 1838, he records then that one of the local men, Noah P. Corn, had built a bridge on the new property in late fall of 1837, presumably to provide access from Crab Creek Road (now Little River Road) to the hillside on which Memminger planned to build. Early in 1838, work must have also begun to create a building site on the steep slope of Glassy Mountain.

Memminger contracted with a carpenter, James B. Rosamond, to construct his house, kitchen, and a stable at Flat Rock, and to, in effect, function as a general contractor. Little is known of Rosamond beyond what can be gleaned from the Federal censuses. He was born about 1810 in South Carolina, probably in Abbeville County where a large number of Palatinate Germans began settling after 1760.

Memminger also brought a stone mason, Patrick Dugan, and a brick mason, John Kenney, from Charleston to Flat Rock to do the masonry work, but he hired a number of the locals, including Kinson Middleton. Kenney and Dugan were in Flat Rock to begin work sometime in the second or third week of March 1838. Both Kenney and Dugan probably worked on the stone foundation, and by early August, it was mostly complete. Probably in August, 16,000 brick were hauled to the site, and Kenney began work on the chimneys.

By the time the ground floor walls were finished in August, Rosamond would have had sills hewn, his sawmill lumber delivered, and if he had not done so already, begun framing the main house. His goal surely would have been to get the house framed, roofed, and “dried in” by the time the rains and cold weather returned in November. It is not clear if work continued straight through the winter, but there was probably a break in activity from shortly before Christmas until around the first of March 1839.

In early April, Memminger paid for 13-1/2 kegs of white lead and a single keg of green paint, which would have been used on the exterior, the initial color scheme of which was almost certainly white with green shutters. Final painting or wallpapering of the interior plaster would have been delayed until 1840 or 1841, in order to give the plaster time to cure, although curing plaster could be given a temporary covering with a water-soluble distemper paint in the meantime.

The major part of the work was complete and the house was at least partially furnished by the time the Memmingers arrived at Flat Rock near the end of July 1839. The house was nearly complete, although there would not be hearths at the fireplaces or plaster on the ground floor walls until 1842. Nevertheless, on 19 July 1839, the family set out for their first summer at Flat Rock, where they arrived on the 27th.

Although work was substantially complete by summer of 1839, the final details of Rosamond’s contracted work were not completed until the fall, and Memminger did not make his final payment to Rosamond until 4 January 1840. He sold the oxen, mules, and wagon in February. Some work continued after that, and Memminger appears not to have concluded his accounting for the original construction of Rock Hill until 1842.

—-

Although Memminger initially referred to the place as “the Buncombe Establishment,” in account book entries in July 1839, he makes his first reference to “Rock Hill,” appropriate enough for a site where stone outcroppings abound.

The house, kitchen, and stable had cost Memminger just over $4,000, but his total expenses for the development of Rock Hill amounted to more than twice that amount by the end of 1842.

Furnishing and Finishing

Edward Memminger, who was not born until 1857, recalled that, because of the primitive, isolated nature of the settlement, “the furniture was made on the spot by carpenters, the same being true of all pioneer settlers,” but that is not entirely correct. Memminger paid a Mr. Buckley some $600 for furniture in 1838 and 1839, and although he has not been documented otherwise, Buckley must have been a local craftsman of the sort remembered by Memminger’s son. The bulk of Buckley’s furniture appears to have been delivered in June 1839 and probably included a number of beds and dressers as well as the large table that would seat twenty-four in the ground-floor dining room.

Memminger also bought furniture elsewhere, including from Harley & Son, a name that suggests a professional furniture company. There were also payments in July to Brown & Oliphant for crockery and to B. Dunham for sash weights, pots, tinware, and and-irons. Most surprising, perhaps, in April 1839, Memminger paid for a shipment of five boxes of furniture that were imported from Germany.

Memminger continued to make improvements at Rock Hill throughout the 1840s and 1850s. A small house for the cook, which the Sandburgs called the “chicken house,” and a wagon house were built in 1842 or 1843, an ice house in 1847, and a servant’s house, the so-called Swedish House, between 1850 and 1853. The ice house was torn down by the Sandburgs in the 1960s, and it is not clear if the “wagon house” still exists. In addition, in 1847-1848, Memminger constructed a large addition to the rear of the Main House and apparently made some alterations to the original interior at the same time.

The Estate

In addition to the land he bought from Baring in 1838, Memminger bought additional property that enlarged Rock Hill considerably during the antebellum period. The earliest was his acquisition of ten acres through a land swap with George Summey, local postmaster and tavern owner who had boarded Memminger and some of his workmen while the house was being constructed.

Two years later, in 1844, Memminger bought a large tract of land a mile or so to the west of Rock Hill. Over the next two or three years, he began developing “Valley Farm,” which would later become his son Edward’s estate, Tranquility. Finally, on New Year’s Day 1850, Memminger paid A.S. Willington (who had purchased from Count de Chisel in 1841) $4500 and took title to the entire 250-acre Saluda Cottages estate. He and Andrew Johnstone then laid out Little River Road, and Memminger cut off the part of the Willington estate that was south of the new road and added it to Rock Hill. Saluda Cottages and the remainder of the property north of the road he sold to the Rev. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, whose son would later marry Memminger’s daughter Lucy.

In 1855, Memminger made his last major addition to the estate when he paid $300 to Henry Farmer to build the dam for the lake at the foot of the hill from the Main House, “which dam I [Farmer] guaranty [sic] to stand without injury from freshets or otherwise for three years from this date.”

—

Christopher Memminger died in Charleston on 7 March 1888. Memminger’s remains were placed on the train to Flat Rock, where he was interred next to his first wife in the cemetery at St. John in the Wilderness. At his death, he had eight children still living.

The house at Rock Hill may have sat empty in the summer of 1889 until the Memminger family put Rock Hill up for sale. On 12 September 1889, Edward Memminger, acting as executor of his father’s estate, sold Rock Hill, its contents, and 292 acres for $10,000 to Caspar A. Chisholm, in trust for Chisholm’s sister-in-law Mary A. F. Gregg.

-

Years later, Memminger’s cousin Caroline Pinckney Rutledge wrote Carl Sandburg with her memories of “a dear cousin” and his Rock Hill:

Mr. Memminger! I wish I had the words and the strength to write them- - a righteous man, grave but gracious; hospitable, generous, bringing out the best in everyone- - high, high thoughts- - fine books- - organ and piano in both homes summer and winter- - Lawns! Bursts of color in trees in October. Lovely lake. Herds of Cattle- - flocks of sheep on the lawn- - Have I left out anything? Oh, yes, conversation most delightful.